This is the term that is used to describe the music that was played and sung in English churches from the late 17th Century up to about 1860. An example of West Gallery music is the tune that we all know for the song “On Ilkley Moor bar t’at”. This is actually a tune called “Cranbrook” written in the early 19th Century by Thomas Clark a carpenter who lived in Canterbury. The tune was written as a west gallery hymn and carried religious words long before it was used for the comic song we all know. The technique of repeating words and overlapping parts is typical of West Galley music and is known known as fugueing.

In the Church of England by about 1600, the only music allowed was psalms. As many of the congregation were unable to read, the parson would call out a line of the psalm at a time and the audience would sing it back. This is a very old way of singing religious songs and is known as lining-out. This technique took on a style of its own with congregations taking it upon themselves to add embellishments to the basic tune. In musical terms the result was probably cacophony, but survivals of this style in the Hebrides and in the Eastern United States have a primitive drive and excitement.

In 1644, under the Commonwealth, an Order of Council of the Church of England was published, decreeing that all organs in churches be demolished, thus taking away one musical element from the churches of the time.

This situation prevailed until Charles II about 1660 when strict puritan ideas were put aside. There were no musical instruments in the churches, but the church was determined to improve the quality of psalmody and so a movement began to put music back into the churches. This gave scope for composers to pour forth a great deal of religious material for use in services. One of these was John Playford better known as a compiler of books of dances, but who also published books of psalm and hymn tunes.

From this point, things started to develop fairly quickly. At first, only psalms were allowed in the churches, but soon hymns not based on the psalms made their appearance. Churches established groups of singers. At first these groups were all male and sang unaccompanied. The style of arrangements was that the tunes were written in 4 parts, with the tenor carrying the tune, underpinned by a bass line and with counter and treble parts above, different from today’s style of scoring for choirs. Choirs then introduced women singers. It was also found that the singers were better able to keep to their part if an instrument played it at the same time. Fiddles in abundance existed in English villages, but it was often up to the church to raise the money for other instruments. The earliest of these church bands had string instruments, but gradually woodwind and brass came into the reckoning. The bass was sometimes provided by instruments such as the Serpent or the Ophicleide.

By the middle of the 18th Century, such bands of musicians and singers were in full momentum in most churches up and down the country. In many churches, galleries for the musicians were built at the Western end of the church, giving rise to the term West Gallery. At this stage, no-one joined in: it was music to listen to, just as you would not join in with a church choir singing an anthem, even if you knew it.

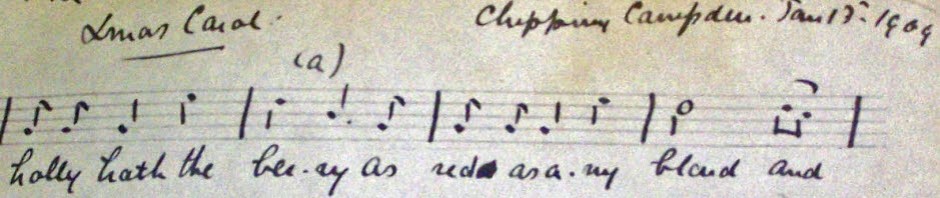

So a typical English West Gallery Quire of about 1800 would include local singers and musicians, with some women singers. They would be very proud of their art, skill and social status. They would play and sing in church on Sundays but the same musicians would be pressed into service for dances and other social occasions. Whilst they would charge fees for playing for dances and weddings, their playing for the church was done out of pride, with occasional gifts of food or drink. Money was very scarce and so rather than buy books of tunes, they would each keep their own notebooks of tunes, words and parts, many of which have survived today and form the core of today’s West Gallery repertoire, although many more have been lost. Because they occupied a special place in the hierarchy of the village, they enjoyed a certain amount of independence from the church authorities. For example, they were generally allowed to choose their own repertoire to sing on Sundays. This independence, in some cases, grew into what was perceived as a certain amount of arrogance. Whilst the church authorities were keen to promote music in church, they had little control over the music or behaviour of their quires. They not only played in church, but had repertoires for Christmas which they played and sang from house to house in the early hours of Christmas morning and thus many of the West Gallery carols start with the words “Arise, arise”. The musicians themselves were probably self-taught and of variable musical skill, but they took inordinate pride in their art and skill and practised for long hours. Furthermore, performance would be based on the style of folk music with which they were familiar, so that the singing might at times have a strident ring and the playing might have a danceable quality.

By the mid-1850s, the church authorities were distinctly concerned about this cuckoo in their midst. Whilst they wanted to encourage worship, they were starting to feel that the West Gallery bands were getting just a little too authoritative and perhaps too secular in their approach to the whole thing. Inspired by the Oxford movement, churches started wanted to seek a return to what they perceived as the status quo ante, namely, music played on the organ, a regular choir in surplices and the whole congregation joining in the music, not just the West Gallery band. These ideas spread as the Industrial Revolution brought more mobility of the workforce and more town-educated clerics moved to country parishes. We can see the result of this in Thomas Hardy’s famous novel Under the Greenwood Tree which details just one such conflict between the new parson and the proud but rejected old West Gallery quire. The result was that many West Gallery choirs just gave up, their old music books were locked away in church archives or in many cases destroyed. The instruments went into decay, or were locked away in church vaults or attics. However, the custom lingered on in many churches until living memory. Apparently the last choir that could have been called a West Gallery choir stopped its activities as late as the 1940s in Dorset.

As well as the Oxford movement, there were other forces at work mitigating against the continuance of the quires. Their style of performance and their musicianship was often called into question, as was their repertoire. The Victorian era was distrustful of what were perceived to be ancient customs.

When West Gallery music was banished from the churches, the performers refused to let their art die. Many of the groups survived as village choirs, singing now not in church, but in families, around the houses at Christmas and, remarkably, in the public houses of the Pennines. The villages around Sheffield have today an active tradition of singing carols in the pubs at Christmas and have their own versions of the carols. A few modern pieces have crept into the repertoire, but basically the carols that you will hear are the old West Gallery ones, passed down in village and family tradition and sung with fervour and pride each year by the locals. Recent research by Dr Ian Russell has lead to the revival of several village groups that had lapsed and it can be said that the tradition is stronger now than it has been in many years.

A similar situation exists in Devon and Cornwall where groups preserve the old village carols. Certainly West Gallery carols have been collected in many West Country villages, and were sung until recently in Shropshire. In Gloucestershire, vestiges of the tradition are found in Ashton-under-Hill (in Gloucestershire until the 1930s) where a set of local carols was kept up until as recently as the 1960s. The nearby village of Elmley Castle in Worcestershire had a similar tradition. It is probable that Chedworth had its own carolling tradition until recently but it is now all but lost. Bisley must have had a recent tradition, and the Stevens family of Bisley until recent times sang their West Gallery-derived version of While Shepherds Watched in the local pubs.

West Gallery music also took on its own form in the United States. The music was taken to the States by the settlers and a carol tradition sprang up in New England based on West Gallery, but taking on a style of its own. The fugueing was still there, but the songs were generally sung unaccompanied. Gone too are the Arise group of songs. Several composers of note such as William Billings were noted for their music. America also produced a unique way of reading the music – it derived from the tonic solfa system, but instead of do-ray-me, had different shapes for each note. This was, and still is, known as Shape Note or Sacred Harp singing.

The situation today

The fact that West Gallery has been rediscovered is mainly due to the efforts of a few pioneers such as Dave Townsend, Mike Bailey and Rollo Woods who have taken the trouble to seek out and teach the old hymns. The teaching of West Gallery music has become a feature of folk festivals and has led to the discovery of even more musical examples as enthusiasts have sought this music in their own area in church archives and in local records offices. The West Gallery Music Association has its own website (http://www.wgma.org.uk/) and has an organisation spread throughout the country. It has several publications to its name.

Note by Gwilym Davies November 2011